Understanding the characteristics of those already engaged with genomics and those who feel confident to practice can inform learning needs and help educators provide genomics education that is fit for purpose. Recognizing the relationships between engagement, confidence to practice genomic medicine, education, and preferred service models may also help define the role of education within broader implementation strategies. Figure 1 summarizes the relationships identified in our empirical data.

In our sample of Australian physicians not trained in genetics, those already engaged with genomics and those who felt confident were both more likely to be pediatricians with recent genomics education experience. The association with pediatrics may reflect the recognized relevance of genomics to pediatric practice28 and/or the close relationship between the fields of clinical genetics and pediatrics in identifying the genetic causes of childhood conditions29. In Australia, clinical genetics services are often co-located with pediatric hospitals, providing greater accessibility; as the majority of our sample were pediatricians, this may explain our finding that respondents were 2.5 times more likely to prefer a model of requesting testing with support from genetics services for inpatients than for outpatients. When examining respondents’ education experiences more closely, there were no associations between having learnt particular topic categories and career stage or location; this suggests that educators can develop programs for broad audiences, without the need to customize content.

Our results suggest that the practice of genomics education should be considered an ongoing or iterative process rather than a single interaction that enables genomic medicine. Prior learning of all four topic categories predicted being engaged with genomics. However, prior learning of topics relating to knowledge or clinical aspects predicted a drop in confidence. Respondents who had completed any form of CGE and were engaged with genomics were more confident than those who had completed CGE but were not engaged, suggesting that education alone is not sufficient to gain confidence in implementing genomic medicine in clinical practice30. It may even be that completing CGE causes a physician to move from ‘unconscious incompetence’ to ‘conscious incompetence’31. Certainly, short-format CGE is not currently designed for, or sufficient to, help physicians move along the continuum toward ‘conscious competence’ and ultimately ‘unconscious competence’. Therefore, perhaps the goal (and evaluation) of CGE for physicians should not be to enable sufficient confidence so that physicians can request genomic tests without support from genetics services but instead to provide a foundation for initial, facilitated engagement with genomics. Practice-based learning supplementary to CGE would then aim to increase confidence over time. As implementation of genomic medicine progresses, opportunities for practicing physicians to become immersed in workplace environments that provide opportunities to gain and apply new genomic knowledge and skills will increase. This will include learning from peers22,25 and supervised workplace learning32 to implement genomics in routine clinical practice.

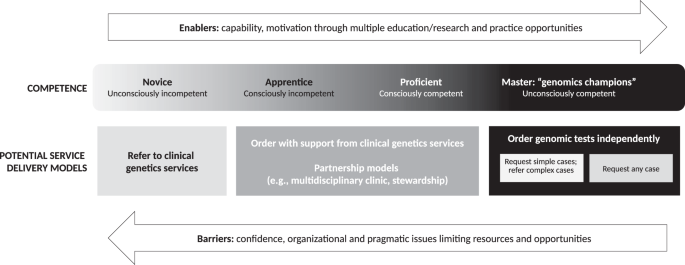

Based on our findings, we propose Fig. 2, where a progression of genomic competence is aligned with a series of potential service delivery models, and education is one enabler of mastery or independence in ordering genomic tests. For example, once a (unconsciously incompetent) learner is aware of the potential clinical utility (relative advantage) of genomics and its value for their practice (compatibility)23, they may undertake education that covers genetics/genomics knowledge, clinical aspects of testing, testing technologies and the associated ethical, legal and social issues. At that stage, a non-genetics physician may realize the complexity of the testing and results, reducing their confidence (conscious incompetence). They may then prefer a service model that involves referral to a genetics service and counselling. The opportunity to practice genomic medicine in a clinical or research setting (trial) or observe genomics through peer-to-peer learning or multidisciplinary teams (observability) could provide additional impetus for adoption33, and a potential shift in preference for service delivery to ordering testing with support from genetics, or similar “partnership” models7,18. Recent Australian education programs offered as part of translational research studies for acute care and renal genomics, have been designed to include opportunities for multidisciplinary engagement (see www.eventbrite.com.au/e/rapid-genomics-in-the-nicupicu-tickets-126912585961 and www.eventbrite.com.au/e/clinical-genomics-for-kidney-disease-tickets-221737010367). Engagement may highlight the speed of change, prompting further physician interest in mastering and maintaining their knowledge, or create the opportunity to shift roles from a type of apprenticeship to more independent practice33.

A proposed alignment between genomics competence and potential service delivery models.

Our results also highlight the need to provide a range of education formats and topics pitched to different levels of competence along the proposed progression, independent of career stage34. This would allow physicians to upskill and refresh their knowledge to complement their experience. It also suggests that educational opportunities to upskill for a new independence may also be more effective at particular stages of a physician’s progression. For example, a physician who has been referring to genetics and observing multidisciplinary team discussions of patient intake and result interpretation may realize that they need upskilling in the particular pathways and procedures for ordering testing, or a physician who is already requesting genomic tests may recognize that upskilling in patient communication and counselling skills is an important step toward independent practice.

Our survey was deployed in 2019, before Australian government-funded exome/genome sequencing (E/GS) testing became available for certain conditions35. At that time, the majority of Australian physicians preferred a future service model where they continued to refer patients requiring genomic testing to a clinical genetics service, for both inpatients and outpatients10. However, we found that physicians who were engaged or confident were more likely to prefer a service model of requesting genomic testing themselves with support from genetics services. With the advent of funded tests, more physicians may become engaged and their service model preferences may change—longitudinal studies would be beneficial. The challenge for clinical genetics services will be to anticipate and respond to this evolution when determining workforce and service delivery. Increased genomic testing by non-genetics specialists increases the demand for genetics services, through both referral and seeking advice7. Unfortunately, the provision of advice to doctors is not currently funded in the Australian health system, amplifying the challenges for clinical genetics services.

Our findings represent perspectives on genomic medicine practice and education from the broadest range of medical subspecialties reported in the literature to date10. However, despite extensive efforts to disseminate the survey, our data represent only 3% of Australian physicians10, and the sample size limited the power of some statistical analyses. Many survey measures were subjective and all were self-reported. Those who completed the survey may have had an interest in genomic medicine, introducing some responder bias, but they are also therefore likely to be potential consumers of CGE, providing valuable insights to guide educators. Questions around prior learning of genomics did not specify timelines, so some respondents may have reflected on medical school teaching, which may have been many years prior.

‘Engagement’ was defined to reflect physician behavior related to requesting or referring for genomic tests, with consideration that engagement with genomics differs by medical specialty, role and external factors, such as test access and funding. In some practices, very small numbers per year might be appropriate as requesting or referring for genomic testing is dependent on the patients seen during that period. Questions about requesting or referring to genetics services for genomic testing were combined in our survey, which limited insights into whether physicians engage with both behaviors. Future modifications of the survey could make these questions independent. Our aim is that this survey, our empirical evidence, and our proposed model of a progression of genomic competency aligned with potential service delivery models, will serve as a basis to understand physician behavior and inform others in defining what constitutes a ‘sufficient’ level of engagement in their local context.

Most respondents indicated they would like to learn more about the topics they had already learnt about, which suggests appropriateness, availability and accessibility of current genomics education offerings. We cannot, however, comment on depth of knowledge required across the topics to progress to the different stages of competency shown in Fig. 2.

Our findings support a medical education model that focuses on outcomes and can be tailored to individualized learning pathways. The model should also acknowledge the value of genomics engagement and experience in both formal and informal settings, and the influence of implementation strategies and service delivery models on education goals and outcomes.