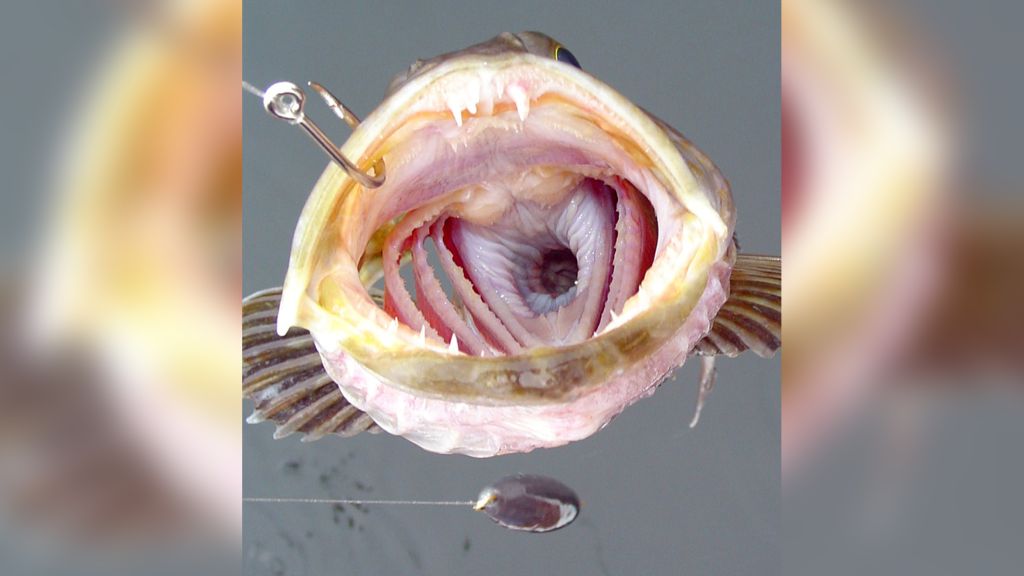

You’ve probably heard that sharks have thousands of teeth, but did you know that there is another fish that also has a huge number of teeth? That is the Pacific lingcod, one of the species with the most toothed mouth, with about 555 in its two jaws.

Recently, a study even found that these fish lose teeth just as quickly as they are teething – they lose 20 teeth a day. “Every bony surface inside their mouth is covered with teeth,” author Karly Cohen, a doctoral candidate in biology at the University of Washington, said.

The Pacific grouper (Ophiodon elongatus) is a predatory fish found in the northern Pacific Ocean. It reaches a length of 50 cm at maturity, but some species of grouper can be up to 1.5 meters long.

The mouth of the Pacific grouper is completely different from what we usually think of the mouth structure. Instead of incisors, molars, and fangs, these fish have hundreds of sharp, almost microscopic teeth on their jaws. Their hard palate is also covered with hundreds of small teeth. And behind one set of jaws is another set of extra jaws, called pharyngeal jaws, which fish use to chew food the same way humans use molars.

A voracious species, the cotton grouper eats anything it can fit in its mouth. When the grouper attacks, its first jaws shoot forward and pull the prey into its mouth, where the inner jaw begins to crush and shred. In order for this strategy to work, the cotton grouper relies on teeth that are as sharp as needles, which however can be easily broken. To keep its bites sharp, its strategy is to constantly grow new teeth. Despite having a strange mouth structure when compared to mammals, the Pacific grouper’s mouth is thought to be relatively normal for a bony fish.

An organism’s teeth can reveal how and what it eats. And because fossil teeth are so good, says Cohen “they are the most abundant artifacts in the fossil record” for many species. For others, their teeth may be the only indication that the species ever existed.

Because so many deciduous teeth occur in the fish’s habitat, the researchers knew about their propensity to lose their teeth, but before that they didn’t know how much “a lot” was.

Cohen and co-author of the study, Emily Carr, a biology student, raised 20 Pacific groupers in tanks at the University of Washington lab in Friday Harbour.

Because the Pacific grouper’s teeth are so small, figuring out how quickly these fish lose their teeth isn’t as simple as counting the number of lost teeth in the tank. Instead, the researchers used dye to create a visual timeline of tooth growth.

First, 20 fish were soaked in a tank impregnated with the fluorescent dye alizarin red for 12 h. Because the red alizarin is attached to the calcium in the teeth, the result is hundreds of teeth with a bright red color. For the next 10 days, the fish were placed in a second dye tank, fluorescent green. Older teeth will be red, while later teeth will be green. In total, she counted 10,580 teeth on all 20 fish. They lose a total of about 20 teeth a day and grow back soon after.

The team also found that the Pacific grouper’s teeth were already positioned, and each tooth would grow back and stay in the same position until it fell out. This is in contrast to the other well-known toothless species, the great white shark, whose tiny new teeth in the inner jaws will gradually move upward before they become larger.

Besides, this species of fish loses teeth and replaces new teeth seems not based on living conditions, feeding, but just replacing teeth over time.

In the calcium-rich waters of the ocean, the researchers say, it’s clear that tooth replacement is a worthwhile sacrifice to help groupers keep their teeth sharp.

This study is important because it offers a more precise way to test tooth replacement that could be applied to other fish species, such as sharks. For sharks, the data came from studies by collecting and counting missing teeth found at the bottom of tanks. But sharks sometimes eat their own fallen teeth (perhaps to recapture calcium), so that data can’t be highly accurate.

A similar study is planned with piranhas.

Reference: NationaGeographic

.