The hypothesis is that for children with conditions, less exposure to bacteria, viruses and allergic diseases will prevent the normal development of the immune system, thereby increasing the likelihood of developing disorders. in the immune system. It is named hygiene hypothesis.

“A child’s immune system needs education, just like any other developing organ in the human body”, Vox quotes pediatric allergist Erika von Mutius, one of the first doctors to research this idea. “The hygiene hypothesis suggests that early exposure to bacteria in early life is helpful in teaching an infant’s developing immune system.”.

Without this information, your immune system will be inclined to attack the wrong target in the case of an autoimmune disorder. The target here is the human body itself.

The sanitation hypothesis is still hotly debated among scientists, but the evidence supporting the hypothesis is accumulating, as we already have examples in both humans and animals. The hygiene hypothesis has been cited as an explanation for the much higher rates of allergies and asthma in rich countries.

Most recently, a 2014 study found that children who grew up in homes with certain levels of bacteria — on cockroaches, mice, cat dander — were less likely to get sick asthma and wheezing at the age of three.

How can being dirty make us healthier? Here is an explanation of the hygiene hypothesis.

From where do doctors think that living dirty helps us live healthy?

Obviously, the fact that human society sets up hygiene rules and technologies to help make life clean brings countless benefits. They are part of the improvement in quality of life, and lower mortality from infectious diseases.

But researchers have found that a few specific autoimmune diseases — such as asthma, seasonal allergic rhinitis, inflammatory bowel diseases and many other allergies — have become much more common as we age. more hygienic. These diseases are more common in rich countries than in developing countries.

In the late 1980s, while studying childhood allergies in West Germany and East Germany, British epidemiologist David Strachan began to suspect an association. He found that in polluted East German cities, children had much lower rates of allergic rhinitis and asthma than in cleaner, more affluent West German cities.

To explain this, Strachan considers all of these lifestyle differences and finds that it is possible that West German children have less exposure to their peers in daycare, in contrast to children’s exposure rates. East German. Strachan suggests that lack of exposure to bacteria and other pathogens, often acquired by other children, affects their immune systems in some way, leading to an increased risk of infection. autoimmune diseases in children.

Proof of the hygiene hypothesis

Decades later, all sorts of epidemiological evidence were gathered to support the epidemiologist Strachan’s opinion. Initially, he found that children in the UK who grew up in large families also had a lower risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis, probably because they were exposed to more bacteria from England. cousins.

Other doctors have found that, in general, people in richer, cleaner countries have much higher rates of asthma and allergies than people living in the developing world. This may be due to the role natural variations play in populations, but more recently, doctors have found that people moving from a developing country to a richer country have The risk of these diseases is higher than people still living in their homeland.

Even in the same developing country as Ghana, urban rich children have higher rates of autoimmune diseases than children in rural or poorer cities. In the rich world, adults who clean their homes with antibacterial sprays have higher rates of asthma, and people exposed to triclosan (an active ingredient in antibacterial soaps) more often have higher rates of asthma. higher rates of allergies and allergic rhinitis. Meanwhile, children who grew up on a farm or had pets had lower rates of allergies and asthma.

Large families can help children have a better immune system.

All of these are not causation but correlations, but they suggest the possibility of disease in a clean environment. Several controlled studies on the topic have also supported the sanitation hypothesis, such as a new study conducted in Uganda. In a study of mothers who were given antihelminthic drugs during pregnancy, their children had a higher incidence of asthma and rashes.

Controlled studies with animals have also provided convincing evidence for the hypothesis. “In experimental studies on germ-free mice in a sterile environment, researchers found them to be more susceptible to asthma and colitis, among other problems.”Vox quotes allergist von Mutius.

Interestingly, though, if these super-sterilized mice were injected with gut bacteria present in normal mice as infants, their risk of autoimmune disease would not increase. Somehow, not being exposed to bacteria in childhood seems to increase the risk of autoimmune diseases in both humans and mice.

How can bacteria help us prevent disease?

The evidence for the hygiene hypothesis has grown as scientists awaken to the importance of “good” bacteria in our bodies in general. The particular species that live in your body — all collectively known as the microbiome or microbiome (term: “microbiome”) — may be involved in the prevention of obesity, diabetes and even even depression.

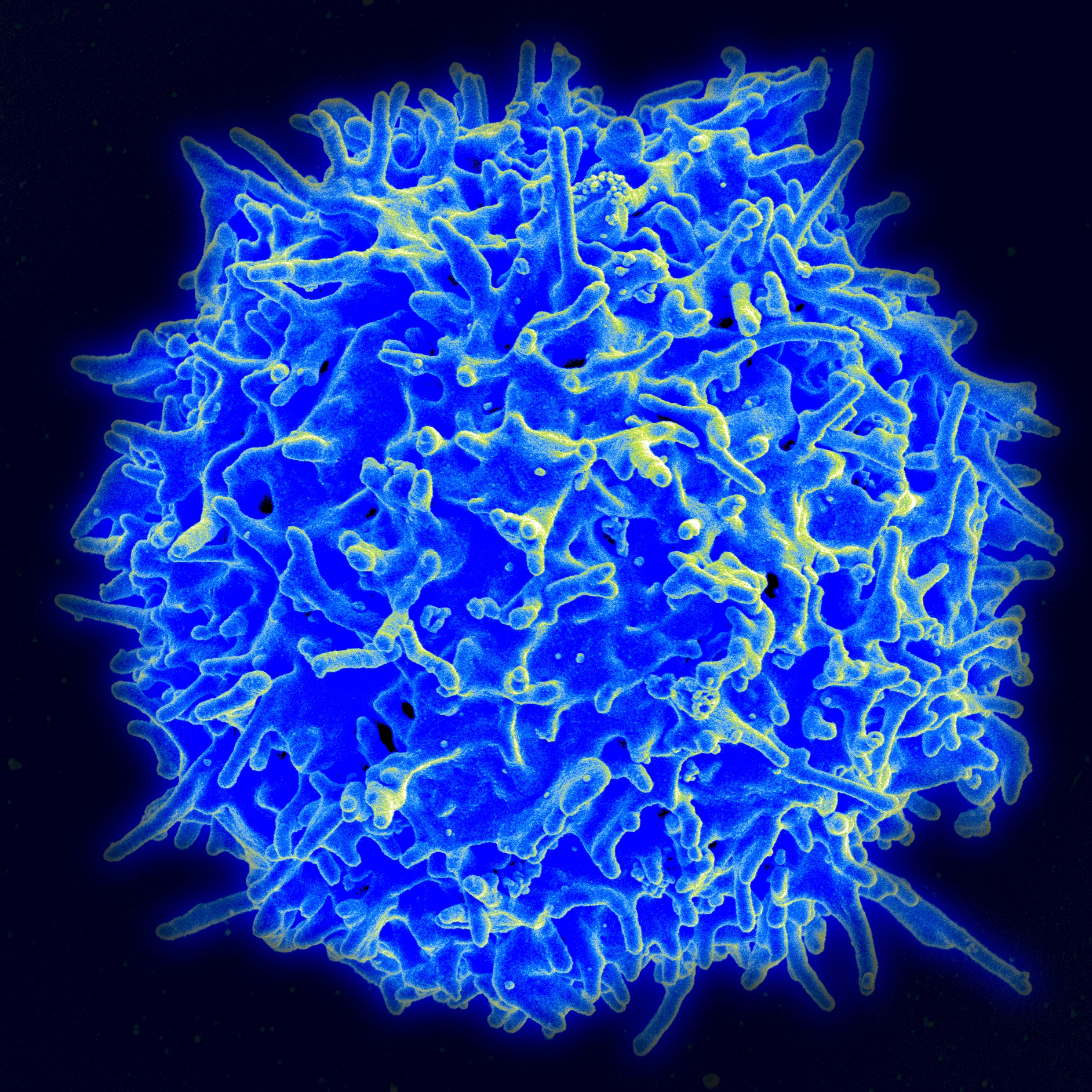

Scientists have suggested several different mechanisms for how limited bacterial exposure might lead to the development of autoimmune disorders in particular. At this point, scientists think the most likely mechanism involves special cells of the immune system, still called T cells.

A T cell in the human immune system under a microscope (Image: NAID)

Also in tests on the same group of mice, the scientists found that clean, bacteria-free mice had large numbers of T cells in the stomach and lungs. Normally, T cells perform many roles in the immune system; They can recognize and eliminate harmful bacteria and viruses. However, in some cases, it was found that certain types of T cells contribute to asthma and colon inflammation in mice. The same seems to be the case in superclean mice that do not carry the disease, because when the scientists gave them a chemical that disabled these T cells, the incidence of autoimmune disease in the mice was increased. super clean significantly reduced.

If a similar mechanism exists in humans, it would explain all the epidemiological findings on these autoimmune diseases and strongly support the hygiene hypothesis.

Disagreement among scientists

For now, the hygiene hypothesis remains a hypothesis: a theory under construction, which will change in the future.

However, no scientist has suggested that the hygiene hypothesis can explain ALL cases of allergies and asthma. Autoimmune disorders have a clear genetic component, so interactions between a person’s genes and environment also contribute to autoimmune disease rates.

In addition, there are some who argue that the hygiene hypothesis may explain the increase in certain types of allergies, but not asthma, in part because asthma rates in the rich world have been lower. increased until the 1980s, decades after present levels of sanitation were established in many places. It may be because some types of asthma are caused by allergic reactions and others are not, and in fact some allergies are aggravated by exposure to dust and poor hygiene. other birth.

Even when it comes to allergies, there are other epidemiological questions that the hygiene hypothesis cannot answer. For example, why in some European cities, children of immigrants from other countries have lower allergy rates than the rest, even though they live in the same conditions. Obviously, we’re still in the early stages of understanding the development of the immune system, and it’s not clear how exposure to bacteria affects that.

Perhaps most importantly, all scientists agree, basic cleaning practices have brought us huge benefits: Millions of lives have been saved by reducing all kinds of infectious diseases, and these may be the most important health advances we have made as a species to date.

So it’s crucial to use research to calculate the right balance between hygiene and microbial exposure to limit the spread of infectious diseases without increasing autoimmune disorders.

What does this mean for us?

None of this means that you should stop mopping or bathing yourself, or start drinking potentially contaminated water from garbage.

For one, most of these conclusions relate to bacterial exposure during childhood – not to adults. In addition, most of the decline in microbial exposure in our modern society comes from larger trends (such as antibiotic overuse and wastewater treatment plants) rather than individual choices.

Therefore, at this time, the practical applications of this research at the individual level are relatively limited. It can make you think twice before giving your child antibacterial soap (which, after all, is something you really shouldn’t be using). More importantly, the hygiene hypothesis provides some evidence that natural childbirth and breastfeeding are important for the development of a healthy infant microbiome.

(Photo: Shutterstock)

But more important is how the hygiene hypothesis should guide doctors’ thinking about the development of autoimmune diseases. In the future, if scientists can better understand the mechanisms of the hygiene hypothesis at the cellular level, we can calculate how to balance basic hygiene and microbial exposure – and the next. Correct contact to prevent allergies, inflammatory bowel diseases, asthma.

Reference: Vox