In a room at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, the invertebrate curator Emma Califf lifted a rock out of a nearby plastic box.

“This is one of our hairy desert guys‘, she said. Beneath the rock was a scorpion nearly eight centimeters long. Its tail curled all the way up to its back and sprouted spiky hairs: A Hadrurus arizonensis, “lNorth America’s largest scorpion“, Califf said.

Hadrurus arizonensis, the largest species of scorpion in North America.

Along the corridor next to the room, Califf introduced me to a variety of other species of scorpions. In addition to that were about two dozen rattlesnakes belonging to many different species. What all the animals in this room have in common: They are all venomous.

Lifting a scorpion out of the box, Califf pinned it down with a pair of tongs. She inserted a small plastic tube at the end of the scorpion, then pricked it with a prepared electrode. The scorpion immediately reacts, wiggling its tail and releasing a clear drop of venom.

Califf collected the amber drop of venom into a plastic tube, closed the cap, and put it in a box. The item will then be sent to a lab at the University of Arizona, where scientists are willing to buy it for $10,000 per milliliter. The number is equivalent to 230 million VND.

Each 1 ml of scorpion venom costs 10,000 USD, equivalent to 230 million VND.

Venomics: The Rise of Science

The preference for scorpion venom in particular and other poisonous species in general is part of a growing trend in a field of science called Venomics. This is the area of research into the protein contained in the venom. The goal is to hunt for molecules with medicinal properties, which can be turned into drugs for humans.

“Going back a century or so, we thought that all venoms had only about three or four ingredients. But now, we know that a single venom can contain thousands of compounds“, said Leslie V. Boyer, professor of pathology at the University of Arizona.

“There’s a pharmacopoeia in the venom of animals waiting to be discovered.”

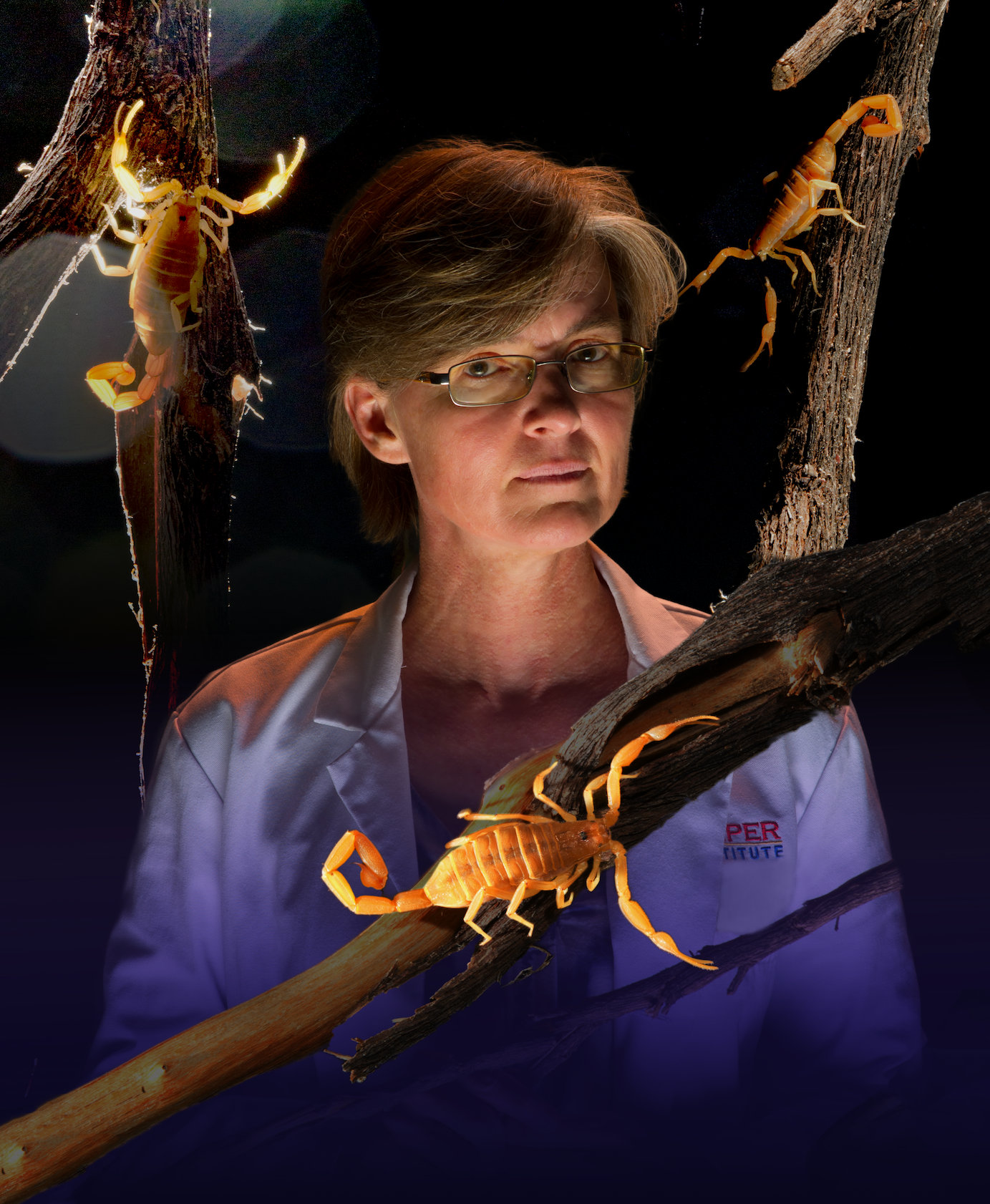

Venom researchers like Boyer are likened to modern alchemists. Their daily task is to extract every microliter of venom from the most poisonous fangs and stingers on the planet. With luck, scientists might find molecules with unique medicinal properties.

Leslie V. Boyer, professor of pathology at the University of Arizona.

For example, one of the most promising venom-derived drugs today was obtained from the funnel web spider on Australia’s Fraser Island. The venom of this spider can easily kill an adult human. But some of the ingredients in it can help stop the cell death process of a heart attack patient.

Scientists found that during a heart attack, blood flow to the heart is drastically reduced. This leaves the cell starved of oxygen, becoming acidic and destroyed from within.

The funnel web spider’s venom contains a protein called Hi1A that blocks acid-sensing channels in heart cells. From there, Hi1A can prevent cell death after a heart attack – something that no current drug can do.

“It looks like Hi1A will become a heart attack medicine“, said Bryan Fry, an associate professor of toxicology at the University of Queensland. “And this molecule was collected from one of Australia’s most vilified creatures.”

Funnel web spiders on Australia’s Fraser Island.

But why venom?

Throughout human history, we have considered venomous animals as enemies, they only bring terror. Although the idea of using poison to treat poison has appeared for thousands of years in some Eastern and Western medicine, few people dare to use the venom of the most poisonous animals in the world to cure diseases.

Humans then only looked for medicinal substances found in plants, bacteria and fungi. We have overlooked hundreds of thousands of poisonous creatures from reptiles and insects to spiders, snails and jellyfish. Even so, their venom is a treasure trove of proteins and chemicals that have been forged through millions of years of evolution.

The first snakes developed their venom about 54 million years ago, for jellyfish, 600 million years. Venom represents a biological arms race, because once venomous species accumulate venom, their prey also begins to evolve resistance.

As a result, poisonous animals have to evolve one step further to create more powerful poisons. Just like that, over millions of years, the most venomous substances on the planet have been forged until now.

The first snakes developed their venom about 54 million years ago.

There is a huge natural library of the organism’s toxins for humans to explore. Each animal species accumulates a different toxin composition. Venoms of each species will vary in dosage, potency, and proportions of ingredients, depending on habitat, diet, and even temperature changes due to climate change.

But in general, toxins will affect the infected organism by 3 mechanisms: Toxin attacks the nervous system, paralyzing the victim. Molecules called Hemotoxins target the blood. And local tissue toxins attack the area around the site of the bite or exposure.

All three of these mechanisms of action rely on proteins to act as key. We as humans are also made of protein, and proteins in our bodies can also be targets of venom, Professor Boyer said.

But if venom can precisely target proteins in human cells, that shouldn’t be the target of drug molecules as well. So as long as we get rid of the toxin and choose the right ingredient to target the proteins, we can turn the venom into a medicine.

As long as we eliminate the toxin component and select the right ingredient to target the proteins, we will be able to turn the venom into a medicine.

Medicines extracted from venom

In fact, there are already several venom-based drugs on the market. Captopril is a drug to treat high blood pressure extracted from the venom of the Brazilian Jararaca Pit Viper snake since 1970.

Another drug is Exenatide, which is derived from the venom of Gila Monster, a lizard native to the southwestern United States. Exenatide is currently prescribed for type 2 diabetes.

Draculin dill is an anticoagulant extracted from vampire bat venom. This drug is used in the treatment of strokes and heart attacks. The Israeli Deathstalker scorpion venom is the source of a compound that is being tested in clinical trials for the treatment of colon and breast cancer.

The diabetes drug Exenatide is derived from the venom of Gila Monster, a lizard native to the southwestern United States.

In March, researchers at the University of Utah discovered a molecule with medicinal properties in the cone snail. In the wild, cone snails often shoot their venom at fish, causing the victim to drop blood sugar to death.

Therefore, the poison of the cone snail is now used to test drugs for patients with diabetes. In a different approach, bee venom has also recently been found to have properties that kill breast cancer cells.

In Brazil, researchers are looking at the venom of Ctenidae spiders to see if it can be turned into a drug for erectile dysfunction. The direction of research was discovered by accident after a man bitten by this spider suddenly became so erect that his penis could not be lowered.

Cone snails often shoot their venom at fish, causing the victim to drop blood sugar to death.

With all this research, the demand for venom is increasing. At the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Califf says she’s scoured remote deserts for unique species of scorpions, where she hunts them at night for these scorpions. Usually glows in the dark.

Scorpion venom is usually harvested by electrifying their tails. While for snakes, what scientists will do is squeeze their fangs against the wall of a test tube and gently squeeze the venom glands on either side of the gills.

Experts hope that, by turning venom into medicine, they can partly change the public’s fearful view of the image of many species of creatures, especially many reptiles. danger of extinction.

Komodo dragon venom can be turned into an anticoagulant.

Dr. Fry himself is now working on Komodo dragon venom, he wants to turn it into an anticoagulant. But the Komodo dragon, the largest lizard on the planet that can grow up to 3 meters long and weigh 70 kg, is also a highly endangered species.

“Working with Komodo dragons allows us to spread the message of their conservation“, he said.You will always want to see nature still around you, because nature is really a biobank. We could only find these interesting compounds from these amazing creatures if they weren’t extinct.”

Refer to Nytimes