The transition from traditional, gas-powered vehicles to new energy vehicles is seen by many countries as one of the most important goals for reducing carbon emissions. By 2020, vehicles with internal combustion engines are expected to account for around one-fifth of the eurozone’s carbon emissions. This is also why the EU is pushing for an earlier transition to new types of vehicles, with the aim of reducing road traffic emissions by 90% by 2050.

Although ambitious, this seems an achievable goal. In a recent survey conducted by the European Investment Bank, more than two-thirds of Europeans said they would choose a hybrid or electric vehicle for their next car. It makes Europe considered the fastest growing electric vehicle market, as well as having the most potential, attracting countless companies including Vietnam’s representative VinFast.

This is obviously great, but the point is, all these cars will have to be charged somewhere.

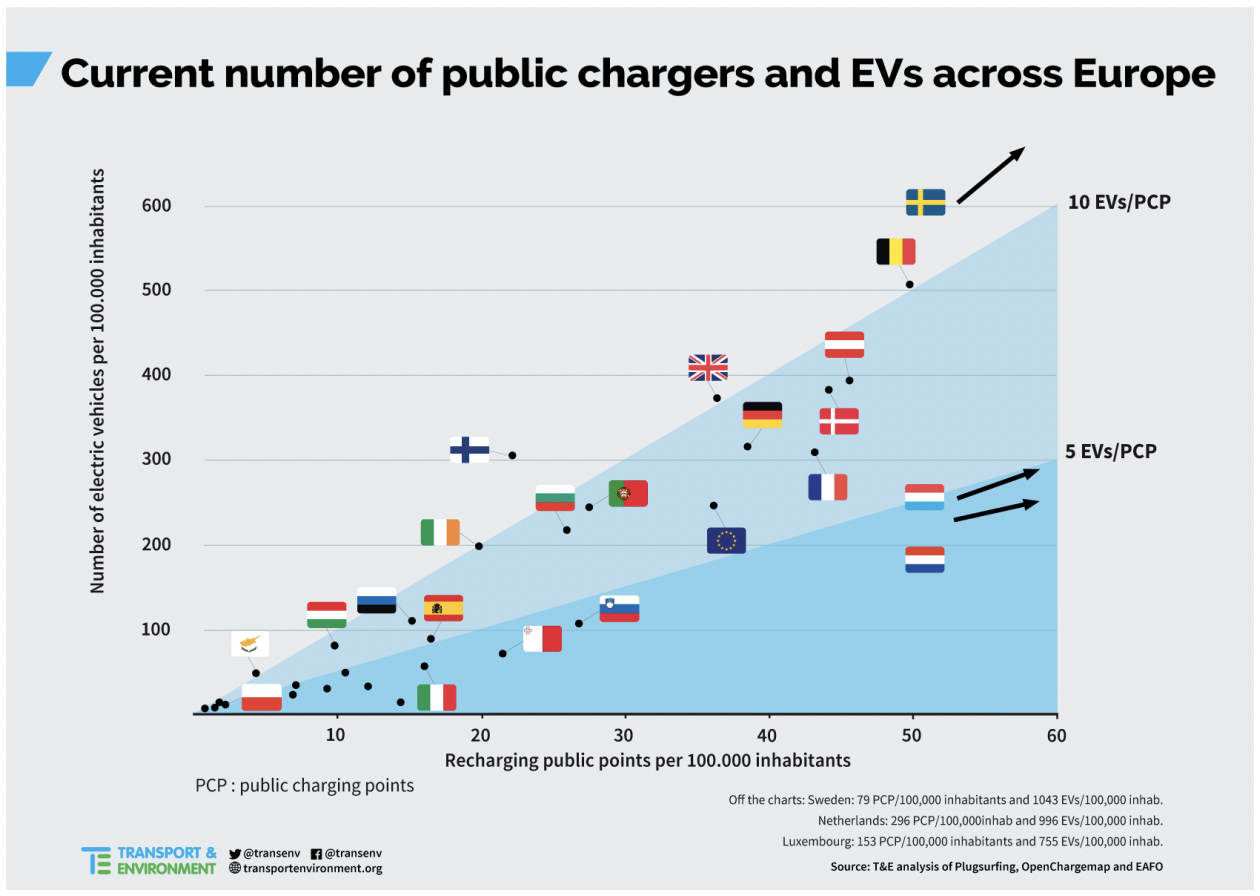

Currently, the main concerns of those considering buying an electric vehicle are still the lack of (fast) charging infrastructure and concerns about the vehicle’s range. These are legitimate concerns, as access to public charging infrastructure across Europe remains flawed. Three countries in Europe alone, Germany, the Netherlands and France, account for 70% of the public charging points across the region.

The big question is how to fix this unequal distribution, and how to do it in a fair and sustainable way. If you think the answer is just “throw money at building more chargers”, then you’re wrong, the solution to the problem turns out to be a lot more complicated than that.

Electric vehicles and charging stations are having the same problem as the chicken-egg story.

What does the market want?

According to a 2021 EU report on charging infrastructure, then “The ultimate policy goal is to make charging electric vehicles as easy as refilling a conventional car battery, so that electric vehicles can travel hassle-free right across the EU.”

And a similar report on Europe’s “Smart and Sustainable Mobility Strategy” identified the need for public charging points by 2030 at around 3 million, with 1 million needing to be installed by the end of the year. 2025. This splits into about 3,000 public charging points per week, between now and then.

Meanwhile, an interdisciplinary study conducted by McKinsey for the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) found that the actual number must be much larger. Specifically, up to 6.8 million public charging points will need to be installed by 2030 to achieve the desired reduction of 55% of CO2 emissions. That is, the number of public charging points for all vehicle segments per week will be up to 14,000, compared with less than 2,000 points per week currently.

But the reports also note that achieving goals is a chicken-and-egg issue. Charging infrastructure construction now lags behind electric vehicle sales, and EV sales have slowed again due to a lack of charging infrastructure.

“Chargers go hand in hand with the vehicle, but if those cars don’t hit the market, those chargers go unused, meaning those charging stations don’t generate revenue.”said Aaron Fishbone, President of Communications for ChargeUP Europe, an industry representative group in the area of charging infrastructure.

ChargeUP Europe has proposed a number of policy suggestions to help try to overcome this conundrum. Among them, the most important is that the deployment of charging stations is governed by a non-binding directive instead of a general regulation for the whole region. That is, each country in the region can choose how they want to implement and deploy, and this leads to overall dissonance.

Because publicly accessible charging infrastructure is largely built and maintained by private companies that maintain and manage chargers. With no centralized planning, each of these companies must find new locations for chargers, apply for permits and then hope grid operators have time to install new connections. . This is a process that can take years and lead to rejection.

The regulation is unnecessarily slowing deployment, says Mr. Fishbone, although grid capacity is rarely an issue.

ChargeUP Europe has suggested some policy suggestions to overcome this conundrum.

Why are charging stations still disappointing?

Consumer friendliness is another problem the industry is facing, also due to a lack of regulation. While the European directive succeeded in establishing standard charging ports, the bigger question was about interoperability rather than physical connectivity.

For example, different charging points require different apps or subscriptions to get charged. And this causes problems with charger availability and billing.

“If you’re going from the south of Sweden to the north of Sweden, you need to download four different apps,” Anna Svensson, head of business strategy at Polestar, shared.

Polestar is currently offering a service that connects different charging station operators, in an attempt to defuse the issue. But Ms Svensson admits there is still a long way to go, largely because operators don’t always want to share data with each other.

The next issue is the availability and reliability of charging points. No one wants to wait in line behind dozens of other cars to wait for their turn to enter the charging station. Then comes the charging point is actually working properly or not.

One charger + one charger two chargers

Another big problem is the charging speed. It takes a while to charge an electric vehicle, especially for long trips. Currently, European countries are still focusing on the number of public charging stations based on the number of electric vehicles or per kilometer. But having a 50KW charger every 100 km is a whole different story than having a 175KW charger with a faster speed.

This way of measuring causes problems. Because different chargers will require different charging times, as well as different fees. And the seamless implementation of slow and fast chargers affects detailed infrastructure budgeting.

Not only that, it’s also important to note that not all charging points are created equal. Green electricity (produced with alternative energy) will have a much larger emission reduction impact than electricity produced with fossil fuels. Instead of simply promoting more charging points, policymakers need to promote more green energy options when building charging infrastructure. Otherwise, the original goal of the conversion will be in vain.

The number of public charging stations varies from country to country.

According to research by Polestar, when using electric hybrid, it will take 78,000 km for its electric models to “break even” or offset the cost of CO2 emissions in the production and construction stages. However, when using green energy, based on energy from the wind, it will only take 50,000 km. The company is currently working on what it calls ‘Project Polestar 0’ which aims to produce a completely carbon-neutral car by 2030.

The future of charging stations

One of the biggest problems right now is that Europe still doesn’t produce enough green energy to meet charging station demand. But policymakers are discussing potential options.

Smart charging example, where the charging station is balanced based on grid capacity, price and availability of clean energy. But this still requires a lot of work on open standards and charging station interoperability. Basically, are electric vehicles currently on the market compatible with these systems?

The future of electric vehicles lies in the widespread deployment of charging stations.

Another open standard being discussed is called Plug and Charge, which should eliminate a lot of the problems in making them more consumer-friendly. Under this standard, payment information will be stored in the vehicle itself, rather than in an app or key, and transferred to charging points when plugged in. Of course, this raises a host of privacy and security issues, which still need to be satisfactorily addressed and standardized.

While it will take time to build the necessary infrastructure and energy to meet demand, there are a few things that charging point operators can do now to provide a wide range of power options. greener.

Some units have actively provided green energy by purchasing renewable energy credits. Others, such as FastNed, have installed solar panels on charging stations to generate their own clean electricity.

“We are still in the early stages of the electric vehicle market,” Mr. Fishbone concluded. “Electric vehicles are not yet a mass market phenomenon. The market is clearly moving in that direction and the transformation will happen. But we’re not at that point yet.”

Refer Thenextweb