If you go hiking in 2022 and lose a shoe, no one will care about your “huge” loss. But also a mountaineer, and lost a shoe in 200 AD, it suddenly attracted the special attention of scientists living in the 21st century.

In a new study under the project The Secret of the Ice (Secrets of the Ice), Norwegian archaeologists have found a shoe dating back more than 1,500 years on the Horse Ice Patch, a mountain pass 2,000 meters above sea level in the mountains of western Norway.

The shoe was once preserved intact in ice, until the unusually warm summer of 2019, the melting ice revealed the timeless artifact. It took three years for archaeologists to restore the shoe and uncover the secrets it holds.

Lars Holger Pilø, co-director of the Secrets of the Ice project, said what they learned from the shoe was published in an internal, unpublished document. “Furthermore, it is written in Na Uy”, he emphasized.

But in an interview with Arstechnica, Pilø openly shared those findings with popular science lovers. Although the shoe is not Cinderella’s, it is still the beginning of a story worth telling.

It was a genuine fashion shoe in Roman times

In fact, this shoe is not what you would expect to find on a snowy mountain. It looks more like a sandal than a hiking boot. The shoe features decorative cuts and a revealing lacing that reaches just enough to the ankle. Far to the southeast of the Roman Empire, it would be a genuine fashion shoe.

Vegard Vike, a conservationist who works at the Oslo Museum of Culture and History, confirms these were common shoes in Roman cities during the 400s and 500s AD – this period is also known as is the Iron Age in Europe.

“The similarity of this shoe to footwear in the Roman Empire is remarkable“, said Pilø.It tells us that people living in these geographically remote mountainous areas still have a connection to the continent. Roman imports have previously been found in Southern Norway (especially weapons), but the shoe tells us that the fashion culture also circulated here.”

The Horse Ice Patch was truly a secluded spot far beyond the boundaries of Rome even as the empire expanded at its height. But Pilø and his colleagues still found Roman influence there.

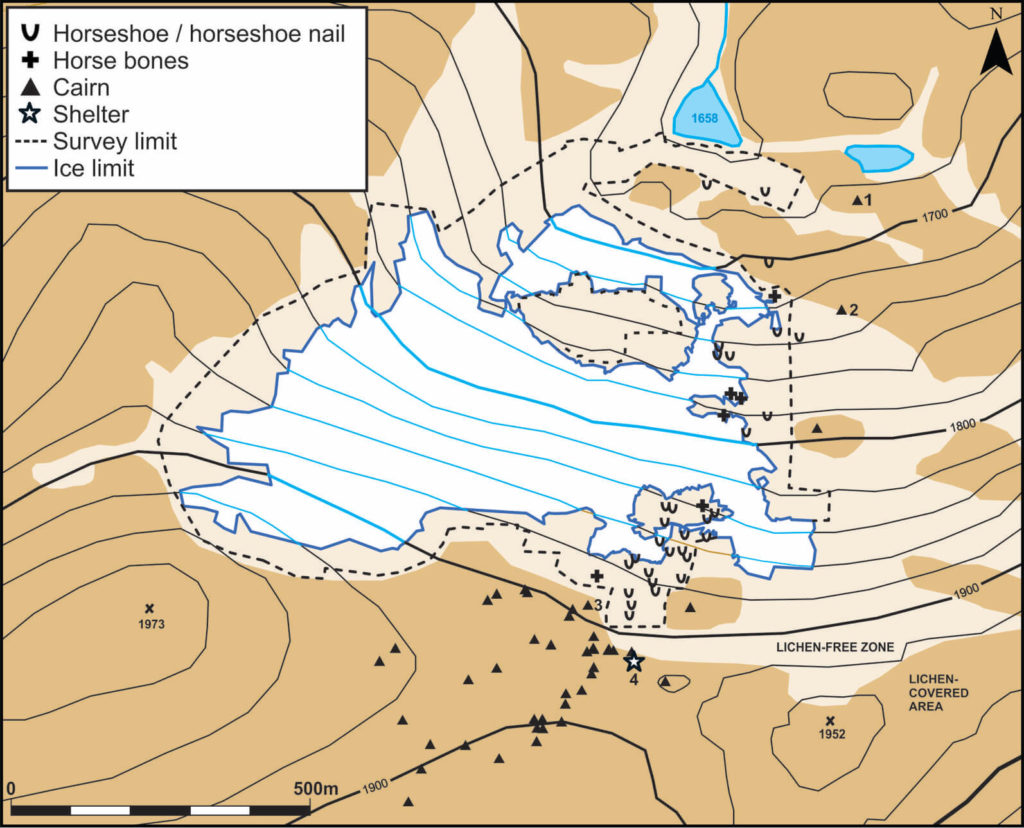

In addition to the shoe, they found many other lost or abandoned items revealing one of the trails that merchants and farmers used to cross the harsh snowy pass. They used it to go to the market or herd livestock on seasonal pastures.

Today, if you just look around the Horse Ice Patch, it is nearly impossible to spot the medieval trails that once converged there. Only artifacts will reveal to archaeologists the paths that people in the past walked.

Near where the Iron Age shoe was found, along the trails in and out of the Horse Ice Patch, Pilø and his colleagues found a 2,000-year-old arrowhead made of reindeer velvet.

They have also found horse dung dumps dating back to the Viking period (about 800 to 1100 AD). In addition, horseshoes and horseshoe bones have also been found from the late Middle Ages. Apparently, the Horse Ice Patch pass used to have a trail that had been used for centuries.

Arrows, horseshoes and an ancient snowboard emerged from the melting ice.

Pilø said to Ars: “The high passes were not used since the mid-19th century, mainly because better roads were opened below them.

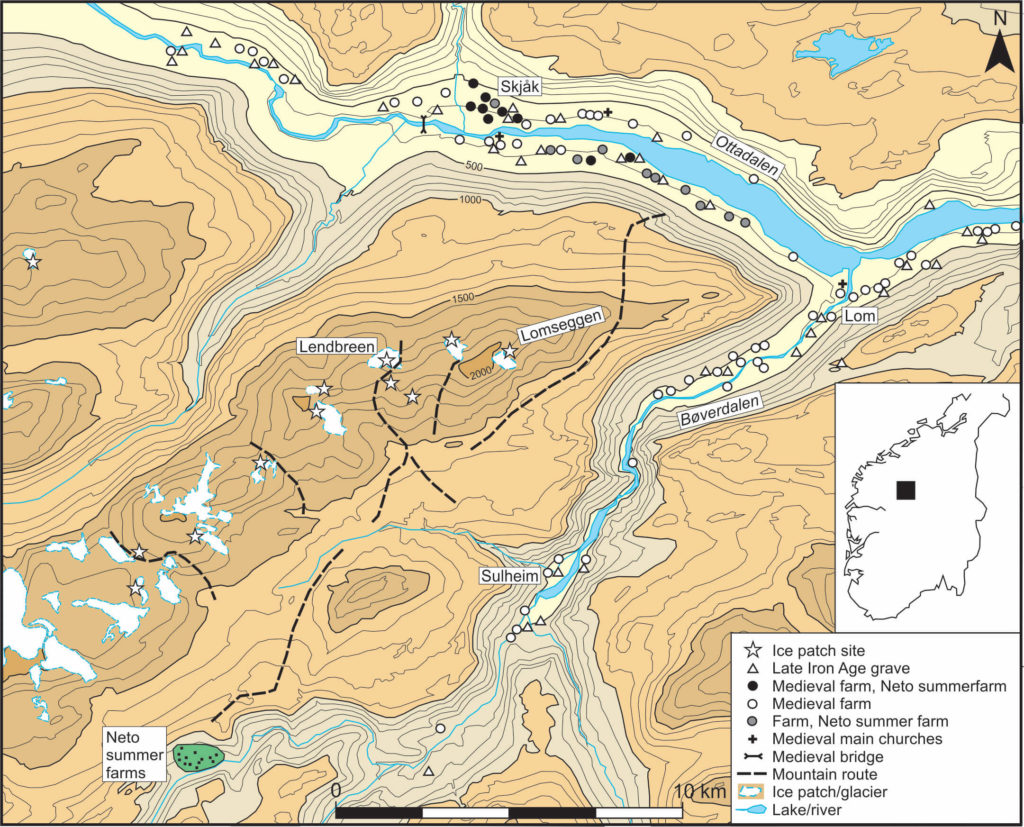

Before that, the Horse Ice Patch trails were the only way a farmer in the Skjåk valley could reach the port town of Sognefjord, Norway’s longest and deepest fjord.

The narrow trails force people passing through it to walk, if they have a pack horse, they must also walk; the terrain is too rough and steep for vehicles to ride, not to mention sleds or carts unusable.

The Secret of the Ice

Pilø and his colleagues at the project Secrets of the Ice has spent the past 15 years mapping the network of ancient mountain routes in Norway. They discovered hundreds of stone pillars that locals in the past had built to mark and rest on the trail.

But over time, many of those old and medieval houses have now disappeared. Or the trails themselves have long been forgotten and have begun to be built up by nature, so they are too rough again. It is difficult to see where these trails go.

Most of the time, Pilø and his colleagues had to track the trails by tracking down objects that ancient travelers dropped or discarded on them. The items are quite diverse, including a surprising number of shoes, some of which date back 3,000 years to the Bronze Age.

Stone pillars mark the medieval trail.

According to Pilø, most of the shoes, including the new one found at the Horse Ice Patch from Roman times, were worn out during the trip, so people threw them away. Obviously, during a medieval pass, one had to prepare a lot of shoes.

When a pair is broken, it is immediately abandoned on the side of the road. In other words, even in a seemingly remote pass that lies close to the edge of a glacier, people passing through it have been littering for centuries.

But here at least, the trash has come in handy, becoming an important archaeological piece of evidence that has survived for centuries.

“If you have a vast wilderness with no trace of humans, but then you realize it’s actually full of clues“, said Espen Finstad, a co-director of the Secrets of the Ice project.Those (junk) give the landscape a whole new story, being a whole setting and not just an item you find in the ice.”.

From farms to fjords

From the agricultural settlements in the Skjåk inland valley in Norway, a trail winds down south and up to the Horse Ice Patch pass. Here, those who follow that path have to climb from the bottom of the valley up to the middle of the mountain at an altitude of 2,000 m above sea level.

The pass is windy, cold and often covered with snow and ice. Up there, a fork in the road opens. One of the two turns leads west, past other mountains before descending into the Sognefjord on the coast.

The camp area of the Secrets of the Ice project team.

Along this western route, Pilø and his colleagues found the bedrock of a bunker that the ancients used to shelter from the wind and snow. It was roofed with sturdy wooden beams to withstand the storm.

Pilø explains: “In the fjord, visitors from the Innlandet region can buy salt, barley and dried fish in exchange for field products such as reindeer antler velvet and agricultural products such as avocados.”.

Meanwhile, a second route out of the Horse Ice Patch leads east to the site of a summer farm called Neto. Along this route, all of the artifacts found so far date to the late Middle Ages or early Renaissance — no earlier.

That said, people probably didn’t use the eastern route before the Neto Summer Farm opened in the 16th century. At that time, most farmers only built one farm. “main” fixed in a place like Skjåk.

The presence of cattle remains reinforces the hypothesis.

Pilø said to Ars: “The basic idea is to move livestock to mountain pasture in the summer so the grass on the main farm’s pasture can be harvested and stored as forage for the winter. On summer farms we have found such leaf fodder that melts from the ice both in Lendbreen Ice Patch and Horse Ice Patch.”

Padded shoes

Going back to the newly found shoe, it was clearly out of place on a dangerous pass, 2,000 meters above sea level and cold all year round.

However, Pilø says that we should not make judgments too hastily. He said the shoes were made from cowhide, and in the past it was cowhide with the fur on. The fur can keep the rider warm and waterproof, and the treated cowhide can add extra traction on ice.

Pilø and his colleagues found much older shoes like those dating back 3,300 years at another site in Norway. These shoes also have fur on the outside. Its former owner even stuffed more hay in it to keep warm.

Archaeologists have also found a 5,300-year-old mummy in the Italian Alps. This person is confirmed to be a hunter known as Ötzi and he also wears a pair of grass boots. Pilø and his colleagues found several pieces of woven fabric not far from the discarded shoe, so he speculates that the wearer may have stuffed the fabric in cowhide for warmth.

“Obviously, shoes like these can’t match modern day hiking boots, but they’re still considered functional and have been worn for thousands of years.“, Pilø told Ars.

And in case you wonder who its owner is, it’s a pity it doesn’t belong to a princess. The shoe was found to be the same size as a European male size 43. It probably belonged to a rather muscular man.

Refer to Arstechnica